My parents were children of Polish immigrants. They came of age in Chicago in the early 1920s and got married in the mid-30s. So by the time they got married they had both been working for close to 20 years. My father had numerous jobs from chauffeur and car mechanic (in the 20s an indispensable skill) to carpenter and picked up numerous other skills along the way. A year or so before he married he secured employment in a small stainless steel warehouse. By the late 30s he was in the Steelworkers Union and continued to work at the same plant, with benefits that today are unheard of for factory workers, until his retirement.

My mother had fewer jobs. Her first was in a meat processing plant in Chicago’s enormous Stock Yards. She told me stories of that horrid place that could have been chapters in Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle. I especially recall her graphic depiction of the one-inch flying cockroaches that swarmed the place. In comparison, the place she worked the longest must have been like paradise to her. She worked for well over ten years at Western Electric’s Hawthorne Works. This was the manufacturing arm of the massive, monopolistic Bell System. All the phones in America were manufactured at Hawthorne.

The prospect of vast revenues generated by the products manufactured for the growing continental telephone system (besides a growing business in electrical devices used worldwide) compelled the Bell System to consolidate manufacturing. This meant that the various, dispersed and small manufacturing units throughout the near West side of Chicago had to be relocated. In 1903, 163 acres were purchased immediately west of the Chicago city limits in a township called Hawthorne. A few years later the township was incorporated as Cicero and became famous as the home of Al Capone.

The construction of the facility grew continuously so that by 1917 25,000 workers were employed researching and manufacturing a huge range of electrical equipment. During the 1910s, engineers at the Hawthorne Works pioneered new technologies such as the high-vacuum tube, the condenser microphone, and radio systems for airplanes. At its largest expansion, 40,000 were employed. To consolidate operations in one large, national facility, workers were transferred from a New York manufacturing center. The main plant was a state-of-the-art building with large windows to let in natural light and an extensive sprinkler system—a first in a manufacturing building. Hawthorne Works was so vast that it had its own railroad to both bring in raw materials and to move manufactured items from one building to another. It also had its own fire brigade and clinic, with a staff of nurses that made house calls when necessary. To keep everything running around the clock, the Works had its own power plant. And besides essential components, like several large dining halls, there was a laundry, a greenhouse, and a brass band.

When my mother worked at the Hawthorne plant her jobs were extremely tedious. She was paid by the piece assembled—as I learned later when she talked about “piece-work” to me as a child, it didn’t mean peaceful work. She told me about one job she did for years which was to spool a fine copper wire over and over again. I’m sure she could have done this blindfolded as she told me that she didn’t have to find the wire but knew exactly where to reach to grab it for the next spooling. The way she talked about the work surprised me and when I questioned her about the tedium she said yes it was, but she could talk to her neighbor and the pay was very good for the time. It was, she said, a job many single women were eager to have because of the financial rewards. This was extremely important as it meant that the women, and it was mainly young women (some teenagers!) who worked the benches at Hawthorne, could afford to live a somewhat independent life.

I was in elementary school when I first heard a story about her job that I found strange. She told me of a time when a group of young college men came to the shop floor with clipboards and stopwatches to time the women’s productivity. This had been a really odd occurrence for all the women.

The scene was hilarious as my mother told the story. All the young women perked up when these young men were on the floor and joked amongst themselves. And, importantly, they got more productive when they were the center of attention. The recording lasted for no more than a few days and then the college guys left for another section of the plant and, of course, the pace of work resumed to the previous rate.

I didn’t realize until I was in college that her story was about the widely known Hawthorne study that Elton Mayo supervised and which demonstrated that workers productivity increases whenever they are the focus of attention. No matter which parameters change on the work floor, productivity increased simply because of the presence of outsiders recording performance. This realization by management led to the industrial practice of institutionalizing systems that promote the sense that workers are recognized for their efforts. This led to the foundation of the Human Resources approach which has been a mainstay of corporations especially after World War II.

I recall as a child, my mother mentioning the Hello Charley Club when in conversation with some of her friends. I didn’t appreciate at the time that some of my mother’s friends were women she worked with at Western Electric and that the Hello Charley Club was a kind of women’s auxiliary at the plant that sponsored dances and events, especially a yearly beauty pageant that led to awards for some women, who were then objectified further as advertising material.

The Hello Charley Club, I discovered, was one aspect of the Western Electric sponsored Hawthorne Club and it is this Club that I began researching for an essay about the beginnings of working class leisure. The Club as I read further into its history, was an amazing institution. First, the worker self-organization of the Club was impressive (within limits, since new club activity had to be approved by management). This led to the second frankly startling fact—the scope of the interests of the workers was impressive. The Club had a chess team and classes in electronics, cooking, and literature. And many more besides. Amazingly, a women’s gun club got approved! And besides these classes there was a huge gym and baseball fields, track courses, and tennis courts. The upshot of all this after work activity was the creation of an autodidactic culture that solidified friendships and enriched the lives of the workers.

What we have here was probably unique in labor history – not the labor history that we all know – but one that is more subtle and significant and under-appreciated, but for a few historians. The Club can be simply written off as a ruse on the part of management to benefit its bottom line, but to do so means not recognizing what the Club meant for the workers.

This essay expanded as the pandemic took hold and I used the time of self-imposed confinement to do more research. With the rise of the concept of leisure as a mass phenomenon the implications of non-work time intrigued me and how free time in the 20s and 30s afforded opportunities for sports (mainly baseball in empty lots), dance hall attendance, and the rise of Hollywood. The next section therefore is on how time has been viewed historically and how it has become compressed by the demands of productivity and platform capitalism. Many workers today experience time dominated by their job.

Time as free-time led me to current studies of play, a field little incorporated into political discourse except as a political provocation. The extensive neuroscientific research into play at first with rats led later to more elaborate studies of the great apes and then, finally, to the behavior of human babies that has major social implications. The neuroscience of play informed developmental psychology and revealed the deep reservoir of behavior that is situated in the oldest parts of our brains. To ignore this developmental aspect of human behavior, which extends back to pre-humans and beyond, is to forfeit knowledge towards a healthy adaptation to well-being.

The notion that play must replace work has been a supposedly revolutionary theme of movements in politics and the arts for at least two centuries (ignoring the classic Greek ramblings) For me this is a false dichotomy. These words, we need to acknowledge, have almost no meaning. Is work toil or a vocation, or is it just a “thing” as in a work of art? Is play just fun, sports, or a way of life? Ignoring the legacy of this semantic problem for now, I think it is best to see “work” and “play” on a continuum. The goal is to strive for play, for a pleasurable foundation to our activities. Even if it is not totally achieved, the premise should be to make toil as free of the misery of domination as possible. In other words, we need to create a radical hedonist culture and abandon the faux hedonism of compulsive consumerism. This is my somber conclusion.

Recent studies of the relative ease of early hunter-gatherer societies, compared to modern stress, reinforce the view that in more recent millennia human capacities have been limited by bizarre mental constructs. The most notable, traditional one being institutionalized religion, superseded by modern systems of sacrifice like nationalism and the work ethic.

The work ethic has become so naturalized that the idea of its history is almost a taboo subject. Some would still maintain that our earliest cave dwelling cousins had to work harder than we do, which has been widely disproven. So why does the work ethic have such an overpowering influence? But at the same time, why does adherence to it become problematic on Sunday night?

What I find befuddling is that while a slew of recently published books have appeared on the topic of work, there is hardly any extended discussion of the work ethic. Unfortunately, the antiquated notion of the primacy of homo laborans still litters the texts of authors on the Left and Right, for different reasons, but nonetheless with equal certainty. Given this situation, exploring the history of the work ethic and how it has changed meaning over time seemed essential after a deep dive into play. A section is devoted to that history and its pernicious effects over the years.

As relief from the dismal survey of the work ethic, a discussion of utopianism enters the essay to juxtapose a vision of a life of pleasurable delights to one of daily misery. It may sound absurd, utopian in the bad sense, given the dire situation of climate chaos and civilization collapse (CC2) to advocate for hedonism. And the issue is complicated recently by explorations of “pleasurable” struggle1 that focus on individual (mainly sexual) pleasure. To me, the individualized focus on sensuality is an essential element of the creation of a positive, healthy outlook on life, but it is not sufficient from a neuroscientific perspective.

My analysis is as follows: An abundant society of pleasure that exists behind the veil of scarcity indoctrination also obscures the premise upon which that indoctrination is based—sacrifice. The false alternative of frugality promulgated by those who clearly perceive the catastrophic consequences of CC2—the advocates of degrowth—needs to be abandoned also.

The quandary of traditional capitalist approaches to the crisis we face is that there is no profit in creating a resilient society, even if we have the time for that. Who will pay for reforestation and rebuilding healthy soils? Who will pay for a new sustainable grid? How will the work that needs to be done (essential work!), get done? With capitalism as an historic failure, why retain the work ethic as obedience to authority? Isn’t it time we recognize that to confront CC2 will require a cultural revolution that draws upon the core of what it means to satisfy individual human needs through pleasurable social relations?

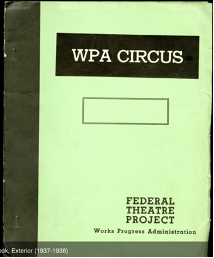

I think that the New Deal era has been exploited for dubious ends. Worthwhile endeavors to alleviate trends towards the destruction of the planet are mixed in with stupid projects—do we really need superfast trains and better six lane highways so we can zip around with our EV SUVs? There is an aspect of that era though that does stand out as one possible template for consideration. The WPA (Work Projects Administration) funded a variety of arts programs including a circus!2 What if that sort of thing was applied to a host of climate chaos remediation projects? I don’t mean financing “Clowns Against Chaos,” but funding, from the government or, better, from local resources, real work, socially useful work, the kind of work that built solidarity through arts projects. The ethic behind those jobs was civic not pecuniary, joyful not grim.

___

1.adrienne maree brown, Pleasure Activism: The Politics of Feeling Good (AK Press)

2